Flushing your pet tropical fish in order to set it free is a bad idea. But so is releasing it into the wild.

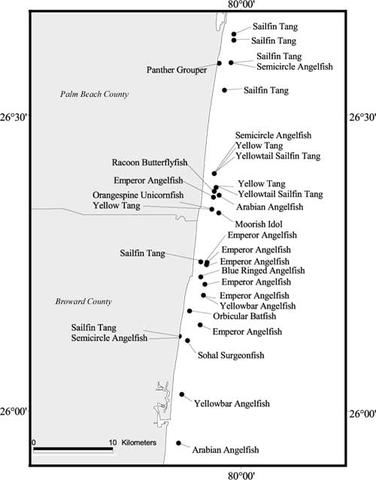

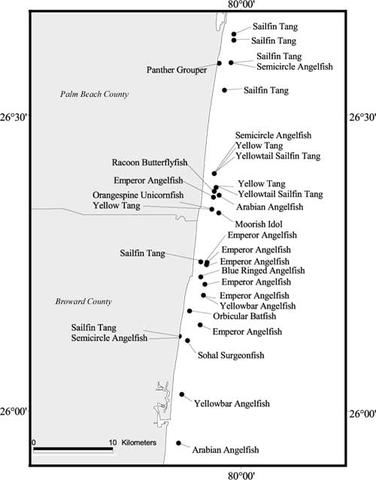

Researchers from the University of Washington and the Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) have reported a “hot spot” of non-native reef fish off the southeast coast of Florida. Divers have reported 16 different non-native reef fish along the coasts of Broward and Palm Beach counties and in the upper Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Many of these species have been seen at several different sites. Using data on the aquarium trade and shipping traffic, they demonstrated that these non-native species are, in all likelihood, the result of aquarium enthusiasts releasing their pets into the wild rather than as the result of ballast water exchange.

“This is an interesting problem because it is the result of well-meaning pet owners,” says Brice Semmens, lead author of the study and Ph.D. student at the University of Washington. “On average I would say that aquarium owners are more concerned with the status of our marine ecosystems then the general public at large. The problem is that there isn’t any mechanism currently in place to educate aquarium enthusiasts about the potential pitfalls of releasing pets into the wild.”

The study, which was published January 30, 2004, in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series, was the result of information submitted by volunteer divers and snorkelers through REEF’s Exotic Species Sighting Program (http://www.reef.org/exotic/). All of the fish species reported are native to the tropical western Pacific and/or Red Sea. While the toxic lionfish has been the topic of discussion in many areas along the eastern US, this noticeable species has not been seen much in south Florida. Rather, the most widely distributed non-native species reported in this study include sailfin tang and emperor angelfish.

Why is it a bad idea to release aquarium pets?

The introduction of non-native species can have devastating ecological and economic consequences. For instance, the release of ‘killer algae’ (Caulerpa taxifolia) from an aquarium in the Mediterranean has resulted in the destruction of large portions of the region’s coastal marine ecosystem. Acres of algal mat now cover habitat that once supported rich communities of fish and invertebrates. While only a small number of introduced species will have such devastating impacts, scientists are unable to predict which species are likely to be destructive. “Releasing non-native reef fish is like playing Russian roulette with tropical marine ecosystems,” says Semmens. Even if the introduced species do not have dramatic impacts, their presence is unnatural and unwanted. Says Semmens, “Divers visit the reefs of Florida to see the region’s natural beauty and diversity. It is a unique and magical experience to dive on these reefs. Adding new species to the region is comparable to adding a few finishing touches to one of DaVinci’s masterpieces. It doesn’t matter if you believe in divine creation, or the balance of nature resulting from the struggle for existence: either way we are messing around with a work of art.”How Can We Fix The Problem?

Semmens and his co-authors point to education within the aquarium trade as the primary mechanism needed to prevent further releases of non-native fishes. Says Semmens, “While it is technically against the law to release non-native marine fishes into coastal waters, it’s a problem that can’t easily be policed. Instead, we need an education program in the aquarium industry that clearly outlines the problems with releasing non-native species and encourages alternatives such as selling or trading the unwanted fish. Armed with the right information, I think aquarium owners will make the right decision when it comes to setting their pets free.”